The gaze of desire in fine art “war photography”: Chauche, el Autodefensor, and non-representational aesthetics

Introduction

This chapter describes the second intervention in which I intend to problematize the idea that counterinsurgency over-determines the possibilities of making synthesis of the present. As already noted in the first chapter, my intention is to explore, through the execution of experimental visual interventions, the possibilities of re-politicizing the structures of feeling on the post-counterinsurgency. Despite a series of contingencies reproducing specific structures of power, it is still possible to carry out radical and self-reflexive thinking taking on the exploration of these kinds of singularities.

The intervention I discuss here allowed me to reflect and ponder on the dynamics of power positions that were at stake during the research process and the dispositions toward collaboration manifested in the same process. This process involved the interaction between the anthropologist and the artist as well as a relation with other subjects who directly or indirectly participate in the creative practice. This is a highly complex endeavor by way of which I seek to explore and expose the dialectical relation of knowledge production with long-term structures of domination such as capitalism and racism. The methodological approach used for this chapter might allow transcending the relation of singularity and potentiality to a moment in which is possible to grasp the fissures of both the multiplicity of cognoscentsubjects and the regime of the sensible.

The importance of studying the relation between historic structures of domination and the emergence of singularities is to evaluate and ponder the power positions and dispositions manifested during the research process in which not only the anthropologist and the artist interact, but also the relation toward other subjects that directly or indirectly participate in the research process. The complexity, in this regard, is extremely high, and we must resist the temptation to reduce it to oversimplifications and/or moral judgments. The aim is to understand the dialectical nature of relational processes of knowledge production and localize it within the long term structures of domination such as the primitive capitalism and structural racism. The production and collaboration with visual artists will be frequently framed in the reproduction of structural forms of power that will affect and be affected by both the social position of the actors, their dispositions and interaction.

These processes are complex and can be articulated in what my former professor, Donna DeCesare defines as the triadic of photography, in which three different photographic events relate to three different kinds of subjects: the protagonist, the photographer/artist/documenter, and the public. This chapter is an attempt to carry out an ethnographic description in which the interaction between these three subject positions is exposed as a complex and very often contradictory process. As I stated in the introductory chapter, my intention has been to carry out non-utilitarian ethnographic relations with subjects interested in producing visual singularities that might allow to re-politicize the regime of the sensible. Some of these processes, such as the one that is presented in this chapter, are more difficult because the dynamic established in the triadic relationality of the photographic event is multidimensional and therefore more complicated than other artistic interventions, such as the recuperation of archival materials, as the one presented in the previous chapter.

This chapter must be read taking these reflections as the contextuality of the specific ethnographic description. In this regard, the participants of the collaboration were basically Daniel Chauche and I, who have a privileged position not only in Guatemala’s society, but also in the field of arts. Other people like Andres Zepeda, Birgit Vleugels and Maria Elena del Valle took part in specific moments of the process.

I can say, however, that our social positions are not that distant one from the other and that the kind of reciprocity established was less complicated than in other cases. In contrast, the debate regarding the participation of the photographed subject, that was the point of departure to carry out this collaboration, don Manuel, became more complicated. Don Manuel is a Maya Mam indigenous former civilian patrolman from San Juan Atitan, one of the most economic depressed areas in Guatemala that suffered of large military control during the counterinsurgency era and had a power position distanced from ours, who were mostly privileged urban researchers.

The complexity of this relationality exposes a specific and paradoxical singularity in relation to the aim to carry out non-utilitarian research methods. The contingency of the post-colonial state/Finca State, the structural racism and counterinsurgency reveals itself in the recruiting process and the photographic event in a crude and realistic way that was registered in the documentary film that was made with Chauche, and which is the point of departure to the development of this this chapter.

In both the film and the ethnographic description, it is possible to trace the remaining of structures of power that conform the complexity of Guatemala’s everyday reality in relation to the production of photographic projects of this nature. In this regard, I embrace classic reflections posed on the dilemmas analyzed by visual anthropologist (Ruby, 1992; MacDougall, 1992) that problematize the processes of representation in the creation of documentaries of oppressed peoples and the debates on indigeneity that question the prolongation of the colonial project in the general project of visual anthropology (Willson & Stewart, 2008).

There are some specificities that must be taken in consideration in order to understand the differences, and possible hierarchies, that can exist between the ethnographic practices and aesthetic performances. In order to critically grasp the reproduction of these hierarchies I consider that, in engaging in non-utilitarian methods and their contradictions, one must settle a challenge to produce reciprocal forms of interpellation. On the one hand, we discussed with the members that took part of this project about the necessity to engage in longer term relations with the protagonists to avoid the reproduction of the colonial project that could eventually yield to capture the protagonist exclusively in the gaze of the photographer (or journalist, documentarist, etc.) On the other hand, we also discussed about the difficulties and gaps that exist between the privilege position we hold in the academia when judging artistic projects that prolong during several decades with the communities.

If we do not pay attention to the ways that artists have articulated their long-term projects, we are also reproducing a form of power that, in general, define the problematic position of the Ivory Tower of academia that criticizes everything without rationalizing its own positionality of privilege. My position in relation to both, the protagonist of the photograph and the artist (Chauche, in this case), can become problematic if I do not make transparent to him that my cultural capital as philosopher, sociologist, anthropologist and cultural critic. This lack would put me in a non-reciprocal relation of power if I try to disapprove other people’s aesthetic and everyday practices exclusively in academic terms. I consider that part of Chauche’s 40 years’ artistic engagement, which include two or three yearly visit to these communities, can allow us to state that he has had an interest achieving relations that are not as superficial as one can imagine from the exterior position of the academic critique of representation. On the other hand, the economic reality of the people living in these places, and the distance that the world of art has from their everyday reality, affects the kind of relationship that can be established (as seen in the film and the ethnographic description, it is not casual that don Manuel, the protagonist of his photograph, wanted money from Chauche). In these cases, the most possible outcome is that forms of utilitarianism will appear, as it is shown both in the film and the ethnographic description. I propose in the last chapter, however, an alternative that might help to relatively reduce the reproduction of these utilitarianism practices. These contradictions must be engaged in the ethnographic description from a self-reflexive perspective.

In this chapter, I intend to analyze other problem, related to the possibility to make visible tat counterinsurgency aesthetics is not only present in contemporary arts, but also that it affects the gaze of the public (including the academia) that reacts to aesthetic forms that are not inherently foreclosed by the counterinsurgency narrative.

The possibility of producing a reflexive intervention with Chauche is framed in the articulation of the triadic nature war photography, in order to destabilize processes related to the formation of artistic visual representations of these kinds of social conflicts.[1]This singularity embodies, in any case, a potentiality to politicize the regime of the sensible in which these kinds of complexities are hidden. Instead of producing a judgment value about this photographic practice, my aim has been to present of these events with transparency, to trigger an ideological interpellation that is largely analyzed in the following pages.

This interpellation contributes to the analysis of non-representational aesthetics in the reconstitution of memory of counterinsurgency. I aim to find the fissure in which the singularity of producing a reflective knowledge emerges and expresses the potentiality of a form of ideologie kritikthat is articulated around the development of visual anthropological processes. In other words, I intend to take the notion of counterinsurgency contingency into a different level, in which the exposition not only of the photographic images, but also the universe of contradictory complexities within it, can produce a break with naïve uses of artistic photographs intended to create meaning related to counterinsurgency.

Building upon a one-year collaborative relation with the French-American photographer Daniel Chauche, in this chapter I aim to analyze the relation between (war)photography and desire as an expression of non-representational aesthetics. To achieve this I have traced an analytical strategy as follows: I summarize Chauche’s life story, and analyze the underlying multidimensionality of his political positioning. Drawing specifically on his white background series of I explore the notion of desire, which I consider can be constitutive non-representational aesthetics. In this regard, the argumentative strand revolves around the idea that beyond representation, the gaze of the subject (the public) —which is intersected by gender, race and class horizons of intelligibility— must be set in some sort of material post-phenomenological—and psychoanalytical—parenthesis. This will contribute to understand the effect of counterinsurgency aesthetics beyond the reproduction and re-inscription of commodity fetishism.

With this premise I explore Chauche’s photographic practice, which is located somewhere in between modernism and postmodernism. In this regard, the photographic event derived from that practice focuses not only on the taking and making of the photograph, but also extends to the production, developing, circulation and appropriation of his portraits. Further, there is a post-poietic and post-cathartic dimension of aesthetics that interconnects both the traditional questioning of exteriority posed by ethical phenomenology, as well as the Ideologiekritikintroduced by Marxism.

The aim of this argument is to analyze the pre-ideological affective moment, where the material and formal constitution of the visual world is not only colonized by a specific affective energy (the wound of counterinsurgency), but also colonizes the forms of perception contingent to the possibility of ideology and therefore the possibility of subject production. In this regard, I draw on Althusser’s (2014) notion of interpellationto understand and problematize the notion of counterinsurgency ideology as the contingency of post-counterinsurgency aesthetics. I consider that the effect that Chauche’s white background produces can be framed in similar terms as the moment when the subject is directly questioned by the authority in Althusser’s allegory of the police saying to the subject “Hey, you, there!” In this regard, however, instead of the intervention of the authority, what makes the subject realize that he/she lives in an ideological world is his propensity to fill up the empty space provided by the background in Chauches photography. I reflect on how Chauche’s white background portraits function as a mechanism to make ideology transparent, as long as the it becomes a space that apparently provides stability to the image and the subject that is suspended within it, but destabilizes the subject (public) that makes from the emptiness a space in which her/his basic desires and anxieties can be located.

Ethnographically, this chapter is based upon a collaborative visual project in which Chauche and a small crew (me included) engaged in several trips to find the most iconic subject in his photography. This project was the point of departure of a relationship that produced a reflective process in which I had the opportunity to discuss in profundity the essential concepts of Chauche’s photography.

A life making portraits

Daniel Chauche started an interesting series of portraits some time before coming to Guatemala. Despite the fact these photos being taken from the front-seat of a taxicab that he drove for a year, these photographs were executed with graceful talent, and gifted skills.

A different character emerged, willing to tell him a new story, during each trip. Sometimes these tales described cases of mental illness, phantasies, phantasmagorias, and under-worldly events. Each passenger was a potential new photographic character. Every day he was armed with a 35mm SLR camera, already pre focused to the distance between him and the back seat, the aperture and shutter speed pre-calculated, as well as a hot flash ready to fire. The photographic event depended upon the passenger’s consent to be portrayed, and to be suspended in the timeless phantasmagoria of portrait photography. Neither the passengers nor Chauche knew they were taking part of a form art that would evolve as it did. For the moment it was enough to know that a visual register of that ephemeral journey was made. The art and the aesthetic attunement came some time later. Chauche named these first portraits the Taxi-Series.

In 1975 Chauche and his former wife decided to travel to Veracruz, Mexico. Their plan was to spend six months exploring that different world, so close but so far away from the American culture. They wanted to spend some days in Guatemala before. They hear from friends it was an interesting and lovely place to visit. They never reached Veracruz. Guatemala was meant to become their final destination. They rented a house in San Juan Sacatepéquez and lived there for two years. San Juan was a small town during those days, where they could develop independent projects.

Neither of them wanted to be moored to academic institutions. Both of them had just finished their university studies. He majored in zoology and she in anthropology, and knew already that academia was not his element. The long and boring procedures to get and process data, as well as to produce research outcomes were bureaucratic and antiseptic. Not his taste, definitely. His sensibility longed for something else than the science cathedrals and ivory towers.

With the prior positive experience of the Taxiseries, Chauche decided to focus exclusively on his photography. When he came to Guatemala, he brought the necessary gear to make both a photo-studio and a dark room. But his plans had to wait some time. The 1976 earthquake happened just few weeks after their arrival. The country was completely destroyed and Chauche was recruited to work as pile loader operator and later as a coordinator in a rural reconstruction program throughout the municipality of San Juan Sacatepequez.

After the1976’s earthquake, when a relative social and political stability was reached in the country, Chauche began his second portraiture project. He named it Foto-Gringo. One day Chauche’s wife decided to sell donuts in San Juan Sacatepéquez. She was interested in establishing a deeper relation with other women in town. Every market day Chauche helped her carrying the basket with the donuts and her petateto seat on. Eventually Chauche planned to take part in the local market dynamic (which happened one day a week) in order to experiment with his photography. That could be a good strategy to resume the course of his photographic career, and to earn some extra money. The next marked day, he brought his medium format camera, a tripod and a framed photograph. He offered his services to the people in town. He wanted to keep this as real as possible. Thus, he thought that the best way to proceed was to sell his services as photographer. By doing so, the people from San Juan would eventually take part in his photography.

What characterizes this second series of portraits depends upon a series of compositions created with a very wide-angle lens. The complete body of the model as well as the contour was meant to fit in the frame. This provided the models the chance to visually localize themselves within their specific ecologies and atmospheres. Chauche let himself be partially directed by the models. They defined most elements in the background, and usually explained to him how they wanted to be depicted in the photograph. His intention during those days was to allow people to openly show the identification they had with their respective locations; the places in which they felt rooted.

Both series, Taxi and Foto-Gringo provided him enough material to compile a portfolio that was the key for him to enter in the Art Program at the University of Florida in Gainesville. There he obtained an MFA degree. During the time he was in the university, Chauche remembers, his major interest was to negotiate with some specific parts of the social and cultural world in Guatemala. He knew already that being a photographer meant not only to master the technique and the complexity of composition. Chauche distanced himself from the kinds of photography uninterested in engaging with people’s worlds; the kind of photography that produces a melancholic gaze of everyday life. For Chauche, the makingof a photograph involves at least some level of inter-affective connection between the people taking part in the photographic event, the photographer and the developing and printing.

That was the basic reason for him to come to Guatemala in 1978. He had to finish his MFA thesis, but at the same time he was dealing with the contingency of his future career. He connected deeply with Guatemala’s western contemporary Mayans. He had all the potential to contribute in raising quintessential questions regarding indigenous peoples, nation-state representations, and non-romantic iconographies. In other words, he was engaged in a project in which indigenous peoples are not represented as remnants of the past. On the contrary, his original project was to show how these indigenous faces are shaping Guatemala’s contemporary everyday life. The concept of contemporary art was still in its infancy, however, Chauche started an early struggle to interrogate the political dimension of contemporaneity within the artistic gaze contingent to colonialism and orientalism (Said, 1978) and the poetics of otherness (Trouillot, 1991.)

After having concluded his MFA and several summer trips later, Chauche finally decided to come back to Guatemala. His first though was he could make a life working as commercial photographer. In 1983 he believed the political violence was declining and that the country was somehow safer than 1982. During that time Chauche continued with his Foto-Gringoseries, and sometime later he also begins a new series of portraits.

These were characterized by the use of more explicit techniques of illumination in the context of a narrower depth of field. This series name is Flash, and focuses on the intimacy of the face that is surrounded by a blurred background and a speed-light frontal illumination. Now it is possible to appreciate a turn in Chauche’s photographic project. He knew that the effect produced by a heavy bokeh (the background blur) that blows away the background provides the conditions of possibility for a blunter intersection of gazes, which would reverberate in a stronger aesthetical effect and, therefore, a deeper political inquiry. This combination would allow him to get closer to the subject.

After the Flashseries, Chauche began the White Backgroundproject. A humanitarian NGO needed a pro bono collaboration for a fundraising campaign for street children living in Zones 1, 4, and 9, in Guatemala City. He felt some dissatisfaction with the limitations imposed by the flash series and shot the first white background portrait. In the beginning he mounted a small studio in the residence of the kids, in Zone 18. Soon after he decided to use the resources of the photographic studio in exteriors. He designed and constructed a set of devices that allowed him to bring the aesthetic atmosphere of the photographic studio in remote and open spaces. He developed a style based on the use of natural light in outdoors. This is the series of portraits that defined Chauche’s most known photography. For Chauche:

…if one is aware, interested and commands an overall vision of the culture, one can recognize within daily life the places, persons or moments that are representative of the culture and the changes within it, that respond to the larger movements within the greater society. That understanding combined with a professional level understanding of photography, or better what needs to be done when making the picture to affectively reproduce the “feeling” that originally drew my attention to the subject photographed.

This was the outcome he was looking for during all these years of experimentation and struggle. After this moment he knew his portraits were not supposed to appeal to any kind of melancholic sociological representation of the photographed subject. He knew his portraits had to provoke an affective reaction tending to dislocate the certainties of traditional ethnocentric gazes. The white background was finally the aporetic space of photography he was trying to construct.

The beginning of an ethnographic project

We were returning from a short fieldtrip to Chicabal Lagoon. Daniel Perera and I offered to assist our journalist friend, Andres Zepeda, to make a video and photo documentation of the misty lagoon. That was the last element for Andres to finish a multi-media chronicle on mestizajeon which he had been working for several years.

Already in my place in Antigua Guatemala we made a quick review of the materials. We spent some time listening to audio samples to combine with the video. We were looking for something that allowed overlapping the harmony of the clouds dancing with the water’s surface. Daniel and I still had to deliver a copy of the materials to Andres, but we needed a couple of days to finish the post-processing work. We decided to meet at Andres’ place three days after.

It was late in the night when we came to his apartment. After passing through the threshold of the door it was possible to appreciate a soberly decorated, unpretentious, space. An atmosphere shaped by Scandinavian furniture prevailed. It was possible to see some artistic treasures hanging on the walls. Two 30x40 portraits authored by Daniel Chauche governed the living room. They hung perfectly centered and aligned on the largest wall. I disconnected myself from the environment, and I was interested only in the contemplation. I was haunted.

The one on the left showed a woman carrying a pack of wood suspended in the air by the mecapalon her forehead. The tiredness in her sight accentuated a three-dimensional face covered by harsh wrinkles. Her crooked body stood with help of a tree branch. Her right arm crossed her body and ended in a closed hand holding the crosier. Her left arm also held the stick and her other hand touched a very delicately smaller hand. This one belonged to a boy, who was about five years old. The boy’s face expressed some mistrust and sadness, bus also curiosity and some interest. She was wearing a Huipil from San Mateo Ixtatán, which was possible to see under a dirty and patched sweater that protected her from the elements. The boy also wore a ratty sweater that was about to disintegrate

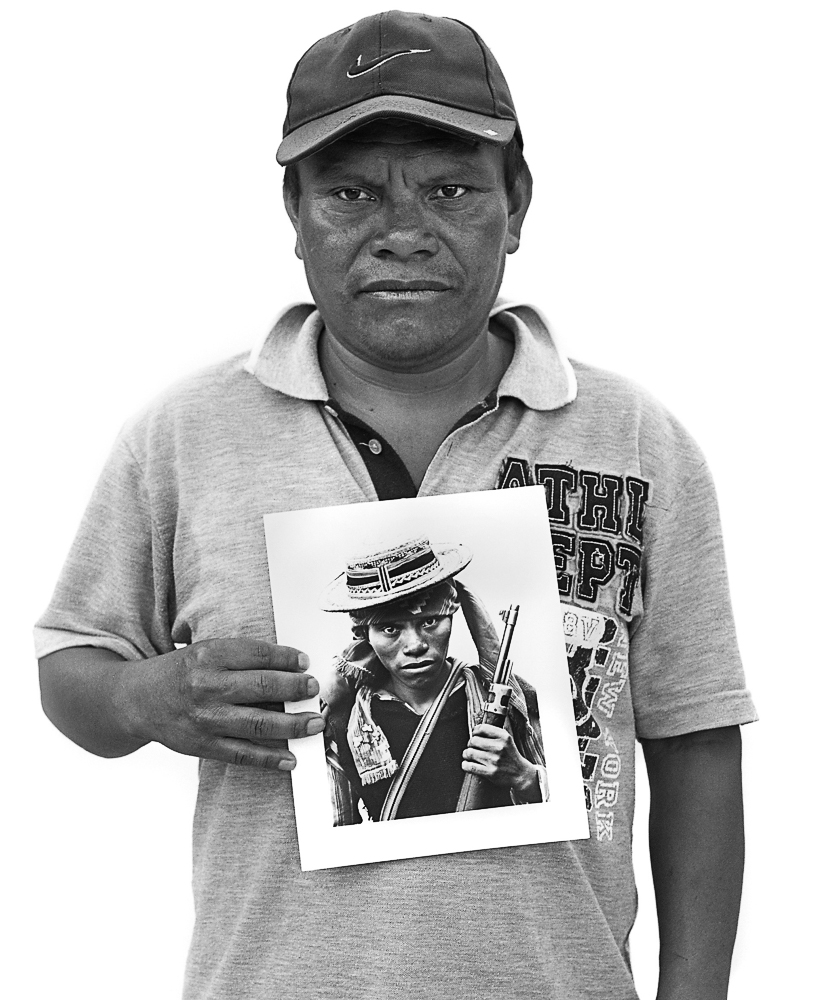

The second portrait was the renowned Autodefensor. It showed a young man fully dressed with San Juan Atitan’s traditional clothing. His hat was mounted on a rag covering his head, in which it was possible to appreciate an embroidery of three delicare flowers in different gray scales. The morral’scord crossed a dark and thick capixay(vest) made of wool. Only one hand appears in the frame, which firmly holds a rifle. Two sharp, beautiful, cheekbones framed a gaze coming from an intriguing, deep, almost inscrutable face. That gaze looked defiant, intense, and defensive. However, after a more careful scrutiny, it was possible to see an expression of mistrust and suspicion.

The three of us stood there for several minutes, to contemplate the portraits. Then, Andres told us that his wife, Birgit Vleugels, bought them some months earlier. Since that moment, they developed a great friendship with Chauche and his new wife, Maria Elena de Valle. Birgit proposed a fascinating idea during a weekend they spent in Chauche’s B&B in Antigua Guatemala. She was charmed with the idea of tracking and finding the Autodefensor. As she told me some time later, she wanted to know what happened with him to understand who this person really is. She was definitely overwhelmed by his gaze in the portrait and asked Chauche if he ever thought of going back to San Juan Atitan to find him again. Chauche had already been working on a project named re-fotografíasince a couple of years already. Everything seemed to fit perfectly.

Andres was aware from some time before of my interest in taking part in collaborative projects that could involve some articulation of visual arts and ethnographic experiences. During the trip we made to the Chicabal Lagoon I told him about my field research strategy, which is based on visual anthropological methods. As described in Chapter Three, I already had experience working with Yasmin Hage, which allowed us to problematize the infrastructural dimension of galleries and the processes of commodification of memory. We could establish a relation between notions like primitive accumulation, the exploitation of the pain of others,and what we later named memory fetishism. I thought that taking part in a project like this might offer possibilities to go deeper in the reflection we started with Yasmin. I was still in the process of preparation of the conditions of possibility to study aesthetics in the aftermath of Guatemala’s civil war. Andres was aware of my interest in engaging collaborative work with visual artists. I explained to him in detail the methods I prepared for the prospectus and also told him that having the chance to engage in a project like that would be a large contribution to my research. He knew I was trying to conceptualize the aesthetical transformations of security infrastructures in the post-counterinsurgency, and he believed that the idea was fascinating.

When we finished the contemplation of Chauche’s portraits Andres invited me to take part in the project to find the Autodefensor. This was not considered on my original research plan, but it certainly opened possibilities to engage in visual-anthropological methods.

I met Chauche some months later. Andres and I went to Chimaltenango to assist him in a new photographic series that he is developing. He wanted to make a quick scout-trip to study the places he could visit later with his medium-format camera to execute a new series that combines portraits and urban panoramas. I was mostly passive during that first occasion. The intention was to give Chauche the chance get to know me. He still had to decide if it made any sense at all to let me jump in the búsqueda del Autodefensorproject.

He did a quick street shoot in the Mercado de Animaleswith his DSLR. It was impressive to see how Chauche moved among the people, the objects and animals. He moved like a fish in the water when talking with the people, requesting consent to make photographs of them, their animals or their market stalls. After finishing the shoot we went to a nearby shopping mall located on the side of the road. We needed to use the toilet and also wanted something to eat. Already there, Chauche asked me some basic questions. “This is going to be a job interview”, I thought. He was trying to figure me out before he officially invited me. “Do you prefer stills or video?” he asked me. “I’m more interested in stills, but I certainly can work with video. I’m not necessarily a videographer, but I know some of the theory and I have some experience,” I replay. “Video is important in this time…”he said, and something draw his attention away.

At that moment Andres came. His face expressed a gesture of desperation and anger; he was pale and his eyes red with anger. He told us that his wallet, and notebook were missing. In that notebook he had all the information to be used to continue his journalistic work on Guatemala while living in Ethiopia. Interviews, field notes, names, addresses were lost. Chauche looked him in the eye. Then, he turned down, looked sardonically his boxers and said: “esas te las robaron de la pantaloneta, vos”. I felt bad about this and offered my help to go back and look for the notebook. Chauche did not ask me anything else. He was still interested in me. Then he said something like: “Andres, we leave to San Juan Atitán in May, isn’t?” Andrés nodded and didn’t say a thing. The annoyance in his face did not despair yet. Then Chauche looked at me and said:”AlejandroAre you interested in doing the video documentation for this trip?” I just replayed“sure, I’ll do it!”

The next day I ordered some extra memory cards, batteries and a new wide-angle lens for my DSLR, and chatted with Alvaro Torres, a very good friend that just obtained an MFA at the Radio Television and Film Program at UT Austin. He gave me very useful technical and compositional advices to create a more cinematic atmosphere in the documentation. He also recommended I take some shots in black and white, to experiment with alternatives to color. I thought it could be a good idea, taking into consideration that the Autodefensorbelonged to a Black and White series. It could match in some dimension with his aesthetical proposal. I planned to make three different kinds of documentation. The first one aiming at the road trip, the second one registering the encounter with the model in San Juan Atitan, and the third one focusing on interviews.

I thought I could advance in a first interview with Chauche during the time we had to spend in the car. These first shoots were made in black and white. In a short period of time he narrated how the original photograph was taken 30 years ago. I learned for the first time how it happened in the context of collaboration with Victor Perera in order to make a photography-writing trip—The Autodefensoris the cover of the book based on that experience named Unfinished Conquest. In that moment I thought of Walker Evans and James Agee (2001) and the trip they made to the American South in the 1930s, which can be considered one of the pivotal moments in the history of photographic documentary style. After six hours we arrived at Huehuetenango. There, Chauche meet with his wife, Maria Elena. We had dinner all together and discussed some last minutes the details to prepare the strategy for the next two days.

Very early in the morning we met to quickly eat breakfast. Then we jumped into Chauche’s car. The trip to San Juan Atitan was about forty-five minutes long. He wanted to be there early to take advantage of the natural light before noon. The plan was to take some photographs with the white background while doing some inquiries to find out if it was possible to find the Autodefensor. I just requested them to make a quick stop to take some panoramic shoots from the other side of the mountain, where it was possible to appreciate the rugged landscape surrounding San Juan Atitan.

Once we arrived, Andrés and Maria Elena helped Daniel to carry the equipment: one half format camera, one white background, several steel tubes that Daniel designed specifically to hold the background, an envelope with Chauche’s original portraits, a blue umbrella, and several rolls of film. I had all my equipment to carry and did not help them.

The first thing we did was to visit the Alcaldía Auxiliar, where the indigenous authorities were gathered. I was amazed because of the quick interaction Chauche and Maria Elena had with the local authorities. They spoke for a few minutes and then went inside the Alcadía. The authorities engaged very smoothly with the project and agreed relatively easily in taking part. There, Chauche and Maria Elena opened the envelope with the original portraits and asked if there were some familiar faces. They helped to find the people in the portraits. Some of them where the autoridadespresent in the Alcaldía.

Chauche and Andres mounted the background in the basketball court, which is in front of the Alcaldía, while Maria Elena spoke with some of the models photographed a quarter of a century earlier. She also asked the rest of autoridadesabout the Autodefensor, whose photograph was circulating from hand to hand in the Alcaldía.

Finally, on the second day, one of theautoridades said he knew him. He lived on the bottom of the mountain. After negotiating with him some minutes he agreed to show us the way to his place. We had to hike down the mountain, find him, convince him, and coming back up the hill. Meanwhile, Chauche and Maria Elena would stay in town taking more portraits.

During those days I was out of shape and I knew since the beginning that hiking up the mountain was going be very painful. However, it was important to have some documental register of the decisive moment of encountering el Autodefensor. It took us roughly thirty minutes to find his place. He was about to eat lunch when we came. The person that guided us called him and they discussed something in Mam. I had the camera ready and started to record the event.

The Autodefensorhad a name now: Don Manuel. When Chauche took the first portrait he wasn’t in the company of any assistant, and could not write his name. Andrés explained to him that Chauche, the gringophotographer that came to San Juan Atitán more than thirty years ago was in town again. “He wants to say hi to you and he brings the photograph of you. He wants to make a new one. What do you think?”he said.

Don Manuel turned to our guide and said something in Mam.Then, he turned back to Andrés and told him a story about this old woman on the other side of the mountain that received two thousand quetzales for a photograph someone made of her some time ago. Andrés replied seriously. He said Chauche would not be available to pay that amount. “He has the original portrait and it is for you”, he said. Don Manuel insisted on the two thousand quetzales. Then, his wife came out and they spoke in mam once again. The only thing I could understand was “dosmile quezale”. He turned to Andres once again and said: “Ok, I’ll go. But I haven’t eaten my lunch”. “yo invito a comer a él y austed, pero arriba”, replaied Andres stating he would invite him and our guide to have lunch up in town. He finally accepted the offer and told us to go first. Andres told him that we could wait for him.

I knew I would not be capable to walk at the same pace as the rest. I wanted to be there when they met again with Chauche, though. Thus I told to Andrés that I would go first to prepare things. Of course I got lost and was the last to come.

We ate lunch and then Chauche did the shoot. It was a long day, but the general feeling was that everything happened too fast and too well. Chauche’s work was done; the photograph was taken. Andres still wanted to interview don Manuel, but not in this occasion. I was taking notes and figuring out the process. During the trip we discussed making several outcomes that would include the new photograph made by Chauche, a chronicle written by Andrés and the documentary, made by myself. We agreed to come some months later in the company of Birgit, who proposed the idea for this project, to make the interview to don Manuel. Then, we could consider our task over. Of course we were wrong.

Producing documentary film while being a photography apprentice: politics of interpellation and non-representative aesthetics

Chauche knew from the beginning that I was interested in both finding don Manuel and in engaging in an ethnographic relationship. I was transparent since the first time we meet that I was interested in using visual anthropology methods as a way to engage in collaboration with the ethnographic subjects. In this case, I was to carry out a research of his photographic project, to understand the dissemination of counterinsurgency aesthetics in contemporary arts. He also knew that my interest in photography was not only academic, I was also interested in becoming a photographer, a visual anthropologist. I knew that Chauche was interested in having a documentary film that registers his production and creative processes. I knew that he was aware of his position in the visual culture in Guatemala and that this collaborative relationship could make a contribution in the consolidation of that position. For him, the documentation of that experience was a means to get a visual register of his artistic process.

Chauche told me to come to his place one week after our trip to San Juan Atitan, because we had matters to discuss. I told him that it would fit better for me to come some time later. I had a trip to Europe planned already and I would be back one month later. Besides, I wanted to organize the material obtained from the trip and, once having that done, we could discuss some ideas of how to edit it. I came on a Monday in the morning and gave him a copy of all my files and a raw cut in which I proposed already the general concepts that would be explored in the film. Because going through all materials was a task that would take a long time, we decided to meet the next day, so that he would have time to see it all.

On the next day I came as planned. He started the conversation saying that he was very satisfied with the results, which expressed in a very accurate fashion his whole process. Then I told him that it was only the beginning and that I had to work much more in this project to get something decent. I told him also that I still wanted to make individual interviews with each one of the participants, including Birgit. It would take some time. He agreed with me and proposed that given my interest in becoming a photographer he could take on me as his apprentice in the meantime. He would lend me a photography book every week that I had to study carefully and he would lecture me about it. Chauche’s main idea was for me to understand matters of composition and form, mostly. He also was very interested in me learning from his main influences and inspirations, as well as the documentary style to which he considers to belong.

Chauche’s documentary style, non-representational aesthetics

I published an essay on desire and Guatemala’s 2015 mobilizations in a local newspaper during those first days of collaborative work. The essay came in to Chauche’s hands and he gave me this speech stating that he was somehow impressed that I had a philosophical education. Then I told him that most of my time in Berlin I studied German and French sociologists and philosophers. He has never studied philosophy and felt that part of my collaboration with the project could be to make the hermeneutics of our discussions.

In terms of style there is a decisive moment that differs largely from what we usually recognize in Cartier-Bresson tradition and/or the schools that look towards the creation of kinds of candidand/or spontaneousphotography. Chauche’s negotiates in a very transparent way with the contingency that make these styles possible, but he partially eliminates the intention of producing a representation of the decisive momentthat generates a replication of a History already defined in sociological or anthropological terms. Chauche’s work is inscribed in the tradition of photographers such as Walker Evans, Robert Frank, William Eggleston, Irvin Penn, Richard Avedon, Flor Garduño, Gabriela Iturbide, Mariana Yamopolsky, among others, who rejected the idea of a spontaneous, verité, photography. For them it is difficult to reconcile the moment the photographed subject poses for the camera and the photographer’s pretentions of producing an image that expresses pure spontaneity, mimics the real, and/or therefore represents it.

This form of making photographs, that borrows compositional elements from documentary photography, but that also positions itself in the impossibility of producing a spontaneous representation of the real, is what Chauche calls documentary style photography. For him, photographs are always producing and/or subscribing to a preexisting narrative that needs to be problematized. This preexisting narrative colonizes the point of view of the spectator. For him, the most important part to use the documentary style photography is to destabilize the naïve of the point of view that considers itself to be in a natural position. To some extent, Chauche engages a project that exists in both the phenomenological transparent experience of the world and the psychoanalytical/ideological specular/reflective reality of the interpelledsubject.

For instance, Husserl’s (1913) phenomenology also intended to produce a suspension of what he called the natürlische Einstelung (natural attitude) by deploying the critical self-reflective phanomenologische epoche, which is a radical form of skepticism intending to suspend every naive idea of the existence of an external, real, world and rejecting the possibility for experiencing metaphysics. To do so the phenomenologist mustin Klammern setzen(to place in brackets or bracketing) every preconceived notion of exteriority in direct relation to the unique position that the observer has in the world. In other words, all forms of exterior reality will depend upon the point of view of the observer and the radical critique to every observation will depend on the suspension and interrogation of that point of view.

Beyond the obvious distances, there is some kind of unavoidable invocation to Husserl’s phenomenology and Chauche’s photographic project built upon the pretention to destabilizing the position of the observer (the suspension of the subject). The difference is that the destabilization of the natural attitudein Chauche’s photographic project is carried out not from a sophisticated philosophical architecture of logical argumentation. Instead, Chauche aims to affect directly the structure of feeling(Williams 1978), which also could eventually yield a modification in what Ranciere (2004) names aesthetic regimes. This is, to perform an iconography that eventually can produce an affective interrogation to the positionality of every one of the people relating with the photograph. And here comes the second great difference between both projects. On the one hand, for Husserl’s phenomenology the illusion of exteriority depends upon rational correlates that exist in the consciousness of the subject (the eye). The world is itself a rational correlate that presents and represents in human’s Bewüstsein(consciousness). And here I believe it is important to point out that the German word for consciousness means both the state and potentiality of humans to recognize their world/environment, as well as to understand it and rationalize it. For Chauche’s photography, the most important aspect to destabilize is the aesthetic/political structure of the world. This is, Chauche’s photography intends to dislocate the potentiality to perceive, to feel, the world in one and no other way.

A fine and perfectly executed photography, which is supposed to make evident that the photographer is making a specific point of view, and that this point of view is everything but neutral is one of his arguments. The other argument is that the point of view of the spectator has something previous that makes him or her to see in the photograph what he or she wants to. And this is the point where Chauche’s photography can also open a debate with the notion of desire, which would be understood in this point of the argument as the potentiality of being a member of a particular affective community. Pharraprasing Ansel Adams, Chauche told me one day something like this: “you never take a photograph, you make it”. In this regard, Chauche frequently questions the intentions of photographic realism and its pretentions to takephotographs in terms of taking something from reality; taking something from the world, which somehow freezes the world in the photograph. He warned me several times of how photographers tend to build compositions that will resonate more and better with specific publics that will be prone to identify these photographs as better representations of reality. To some extent, this is something similar to what Sontag (2004) points out in her essay Regarding the Pain of Others and the processes of loss of sensibility produced by the massification of war photography.

As far as he considers himself to be in some liminal space-time between modernism and postmodernism he rejects the idea of pure representation in terms of politics of aesthetics and/or aesthetics of politics. Chauche pointed out to me how frequently documentary photography tends to produce forms of romanticization of others, which essentially are forms of production of the real that, in the worst case-scenario, could be considered orientalist. He continuously struggles against pretentions of both pure realism and romanticization, which he considers to be opposite sides of the same coin. And the problems here do not only lie on the moment of the composition and the fabrication of visual representations, but also in the social space of identification where the image will be received.

This is the basis of the clear distinction he makes between documentary photography and the documentary style photography. While documentary photography pretends to mimic the real of a particular event, documentary style photography inhabits the aesthetics contingent to the impossible world-reality. Building on this, Chauche proposes that his focus is not in producing meaning, but instead in problematizing the eternal projection in the photographs of people’s own hopes, demons, dreams and nightmares. This perhaps the distinction that Lacan (1978) recovers from Merleau Ponty (2013) to differentiate between the eye and the gaze. In other words, we could say his project negotiates with the aporiaof the real and its radical substitution for a politics of desire, which could be found in Lacanian psychoanalysis that returns to the realm of the hermeneutic, imagination and symbolism.

The position Chauche inhabits in his photographic project is built upon a mixed mood of frustration and fascination regarding the reaction of most people to his work. One the one hand, he feels frustrated how critics, curators, dealers and the public in general would not have a finer sensibility to understand the line that separates a pure documentary photography from a kind of fine-art photography that stylistically borrows from documentary photography. On the other hand, he feels fascinated by this lack of sensibility shared by these differentiated subjects because that is the event where it is possible to appreciate the political radicalism of his aesthetical approach.

I mentioned above the idea of a different kind of decisive moment. In this regard, I propose that the paradoxical relation that combines both frustration and fascination in a single affective frame embodies also a kind of radical critique of representation. The documentary style Chauche advocates for emancipates itself from the need of representation as a starting and ending point in his aesthetics. This decisive moment does not depend upon a fraction of a second determined by the mechanical impact of the shutter that captures THATmoment, piece, or part of reality that the image mimics (almost everything will be staged), neither the intentions of the photographer to localize the subject in a particular landscape/geography (Thrift 2007) from where sociological conclusions can be drawn. This is a moment when photography becomes deconstructive in a non-discursive and a non-logocentric (Derrida 2016) sense. This is, an event located in a sort of ethics of the face, which in Levinasian (1969; 1998) terms is both inaccessible and infinite; an event that interpellates the point of view of every single subject—the public as well—taking part in the production visual meaning. In other words, the point of view of all subjects that believe that a particular image (or a series of images) produces a specific meaning that represent reality is to be questioned.

All these debates also affected me deeply. The photograph that interested me mainly, and that pushed me to adventure in an ethnographic collaboration with Chauche was the Autodefensor. In some extent I believed it would be possible to find in this collaboration some kind of validation of my preconceived points of view or hypotheses regarding aesthetics, infrastructures of security and postcounterinsurgency Guatemala. My point of departure was biased towards the processes of representation and understanding of civil war and war photography. My desire was to find in Chauche’s photograph a history of war that eventually developed in sime kind of history of securituzation of Guatemala’s everyday infrastructures.

My original idea changed enormously. For me it was more plausible to think now that instead of being a documentary photography portraying specific moments of civil war Chauche’s documentary style tends to permanently evolve into some sort of non-representational aesthetics that could be in discussion with some of Thrift’s (2008) arguments. In any case, this aesthetics is not necessarily focused on producing and/or reproducing discourse, pure description; instead it intends to explore the affective disturbances that Chauche’s portraits produce in the affective ambient—this is similar to what Kathleen Steward (2011) names atmospheric attunements. These attunements are, I believe, discussing already more explicitly with an anthropological debate of aesthetics in a non-representational sense, which somehow would be pre-ideological. This means that the space of affection of affects precedes what Marx (1980, 1992, 2016) would performs as Ideologiekritikin his theoretical development. I would like to dig a little deeper in the ethnographic experience to unwrap this argument.

Collaborative documentary: making ethnography of the white background?

I came back to Guatemala a month after our road trip to San Juan Atitan. We met, as planned, in his place at 11:00am. I came with a copy of all materials—I wanted to store a copy of all videos, audios and photographs in his computer to prevent the case of my hard drive failing—and a raw edition in which the structure of the documentary was already settled. I made a very simplistic organization of the materials, placed all the scenes together and classified them using this sequence: First, road trip; second, everything that could help to produce a visual contextualization of San Juan Atitan; third, all cuts from the process in which he and his wife interacted with the indigenous authorities in order to identify the previously photographed subjects; fourth, everything related to the moment of reencounter with El Autodefensorand the final shoot. During that moment I still believed this collaboration would help me to create an ethnographic narrative about war-photography. However, things got more complex.

Officially, I was already Chauche’s photography apprentice and I had to come to his place every week or two. I understood his idea of having weekly meetings was twofold. On the one hand, he would school me in photography so that I could understand the implications of the documentary style photography (by the time I still was unaware of the hermeneutic process described in the previous section) as well as to improve my photography. On the other hand, we would work further in the edition of the documentary in order to get a product based on a deeper interaction between us. Eventually, we would go also to shoot together in Chimaltenango.

One of the things I considered very important was to carry out a series of interviews with him, Maria Elena, Andrés and Birgit. We could advance the first two interviews before Andres and Birgit came back to Guatemala. We planned a second trip to find don Manuel, in order facilitate Andres the conditions to interview him. His part of the deal—the journalistic chronicle—depended upon it. That moment would be also the opportunity for me to interview Andres and Birgit.

I planned the interviews to Chauche and Maria Elena relatively soon after my return from Europe. Maria Elena provided detailed information about the process involved in coming back to the communities after so many years, finding the subjects, gaining their sympathy and trust, and making from the whole experience something pleasant for everyone, where everybody feels not only comfortable but also emotionally engaged. Chauche’s interview focused mostly on his artistic processes and evolutions, which I basically described in the beginning of this chapter. It was the moment when he, for the first time, uttered that he was not interested in producing sociological or anthropological representations of indigenous peoples, the civil war or everyday violence. Instead, his portraits were meant to produce something he names a psychological effect that intends to interpellate the normality in which every body believes they live.

As pointed out in the beginning of this chapter, the three most representative moments of Chauche’s photography involve a struggle he had for several years to understand the implications of positioning the portrayed subjects in different backgrounds as well as to understand the aesthetical and political consequences of each variant. Foto Taxiwas a project in which the subjects were positioned on the backseat of the taxicab. In Foto-Gringo, he requested the subjects select the location for the composition in order to consent with them the place they would like to be identified. During these series it was possible to see everything in detail because of the use of wide-angle lenses and large depths of field. During Flashhe started to blow away the context by using a longer lens that, combined with a frontal speed-lite, blurred considerably the background. Finally, in Fondo Blanco (white background)he completely gets rid of the surroundings by placing a white background that isolates the subject in a very dramatic way. This Fondo-Blanco series is where he finally feels satisfied with the kind of aesthetic attunement he has been trying to achieve for several years.

Of course there is a strong influence of Richard Avedon in this series, but there is also something very specific and authentic in the process that brought Chauche to this point. Everything that came before this series was a process of trial and error that would cause huge internal aesthetical dilemmas in Chauche’s creative process. He felt that by presenting the photographed subjects without any background he would finally find the kind of identification he was looking for. This identification was the impossibility of representing the real itself. In conversations we held in his car during a trip to Chimaltenango Chauche told me something like this:

Most people don’t understand what I do. And that’s good, you know. Even people highly educated in fine arts frequently think that my white background photos tend to romanticize the subjects I’ve been working with for so many years. What I have intended to do is to produce a kind of photography so finely executed that, to some extent, it would force people to ask themselves “what am I seen here?” “What is expected from me in seeing this photograph?” Most of these people will never realize that what they see in these portraits is a person like them; that inhabits a space very close to theirs; that are very similar to them. And that is, I think, because they do not have these reference points in the map that explains the whole story. They try to compensate for that lack of context that the white background produces with some political narrative. People tend to project their own politics into the empty white space behind the subject.

My hope was that the production of this documentary film would allow me to articulate somehow this point Chauche expressed so clearly in the car that day. However, the struggle I had with the documentation materials, the contents of the interviews, and the specific interests he had in making a documentary film showing his work created a larger distance from that goal. Chauche needed something very specific that could help him to present the experience we had in our search for the Autodefensorthat would also be a way to introduce the general public to his work. On my side, I wanted to make an ethnographic film that would pose these questions about the critique of representation, interpellation and destabilization of aesthetic hegemonic infrastructures.

A few months later Andres and Birgit finally came back to Guatemala. We prepared the trip so that everybody could go to San Juan Atitan this time. Andres would interview don Manuel; I would video and audio record the interview. Later, I would also interview Andrés and Birgit. I thought this would be a good time to fill the gaps I still had unresolved. This would help me to eventually achieve the aim of doing an ethnographic film on the complexities of war photography and its aporeticmoments. Chauche allowed me to understand that war photography was frequently based on the community of feeling for whom the photograph was taken and that somehow the representation made in the photograph would correlate with the space of desire and affective identification defined in the community of feeling where the photograph circulates.

Chauche and Maria Elena would not be available to come until the next day. I traveled with Andres and Birgit. Already in Huehuetenango, we went out to dinner in a local Italian restaurant. We prepared the interview for don Manuel just after eating. The plan was to make a structure where Andres could question from the general context he was living in 1989 in order to, later, question him about the specific moment when the original photograph was taken.

We were back in San Juan Atitan in the middle of November of 2015. This time we did not find any indigenous authoritis in the Alcaldía Indígena. There was no Mercadoday either. The aldeawas partially dessert. We had to walk all the way across the mountain once again to see if we could find don Manuel. It was a matter of luck. We had a telephone number to call a relative of his, but nobody answered. We did not know if he would be there. This time we did not have a guide either. We asked some of the few people in town until a woman told us that she was going down the mountain. We could come with her if we wanted to. She barely spoke Spanish and we did not speak any mam either. It was uncertain where she was leading us. In the middle of the way she told us she had arrived her destination. Then she told us goodbye. This time our luck was different.

I came close to Andres and told him: “do you think we can find the place?” he looked very skeptical and answered something like: “We’re screwed but we don’t have any alternative?” We were lost for about three hours. It was a very steep mountain. The corn crops created a tridimensional maze that made everything more difficult. We were lost in a three-dimensional space. I thought it would be easy if we only walked down. There was a river, which we could follow until don Manuel’s house. However, when you are lost in such a mountain, things will never be that simple.

After three hours we found don Manuel’s place. We were exhausted and unmotivated. The morale was very low. We traveled so long that we had to finish our task, though. We would not have any other chance in the near future to return. Birgit was supposed to leave next week back to Ethiopia.

We were in don Manuel’s patio when his wife told us he was doing seasonal work in the sugar-cane fincasin the bocacosta. The frustration was shared. “At least we get to show her the part of the film we have advanced. She appears there…” I thought. She only laughed when she saw it.

On our way up to town I had another experience. My physical condition was not better than the first time we came to visit. The difference this time was that we got los for so many hours. I did not have any energy left to go up the mountain. It was very embarrassing to see that Chauche and Maria Elena (both over 60) did not have any trouble hiking up that mountain. I was delaying everybody. I told them to go first. I would come some minute later. It was better. They left and Andres stayed to walk with me. We came up half an hour later.

We were very surprised and happy when finding out that Chauche came across don Manuel by coincidence when he was already up in the town. Don Manuel was coming back from la Mesilla (a border town between Guatemala and Mexico). He escorted his nephew, who just migrated to the U.S. He seemed to be happy to see us again. We told him that Andres was interested in interviewing him. We went to eat at the same place we did the first time. Andrés asked me to show him the advances we had of the film. I took the computer and my hard drive out of my backpack and played it. He did not give much attention to it.

Later, Andres and Birgit engaged in a conversation with Don Manuel. They intended to explain to him the whole project and the relevance of the interview. They convinced him relatively quickly. His only concern was the language. His Spanish was not fluid and our Mam inexistent. I settle the audio recorder and mounted my DSLR on the tripod. Chauche distanced himself from the event. Although he was very interested in knowing what could come out from that experience, he also knew that the interview was not his task. Andres was the one who had to write the chronicle. I was recording in order to document the process, which eventually could also be used in the film.

After we finished the interview, don Manuel asked if we had some dollars in our pockets. This time he was not asking for the original two thousand quetzals. Only the change we could have in our pockets. I was the only one with twenty dollars in my wallet. I handed the twenty dollars to him, and we left.

The outcome of the interview was basic. The linguistic and sociocultural gap between Andres, Birgit and don Manuel was very large. The information we obtained was not extensive. It helped mostly to corroborate some of the data we had from the beginning. Perhaps our expectations were too high. Chauche told us on the first trip that in such a project it is better to keep the expectations low. Of course we heard him but did not listened. We expected a coherent and completed story about the context in which the photograph was taken. We wanted a story of the autopatrulleroa story of the war and counterinsurgency violence. To sum, we wanted to fill the white background of desire that Chauche criticizes with his photography.

Perhaps he did not want to talk about it because he barely knew us. Perhaps we should have planned the interview using an ethnographic and not a journalistic approach. We could not answer the questions that the interview arose.

The next day I interviewed Andres and Birgit. Those were the last pieces I needed to finish the film. Andres’ point of view was mostly determined by a sociological analysis. He focused on the transformation he had experienced between the moment he saw the photograph for the first time and now, when he could be finally available to fill in the white background with socio-economic realities, which to some extent were also subjected to our ideological desires. He spoke about structural violence for a long time and correlated that violence with the Autodefensor’seyes. He said that it was a gaze that look you in the eyes and questions you.

There was a strong coincidence between some of Birgit’s and Andres’ arguments. Both commented on how the autodefensor’sgaze interpellatedthem in several levels. However, something very specific emerged from Brigit’s interview. She remarked on how this Autodefensor portrait—but all the white-background series in general—entails a critical questioning of her position in the world as well as her general social, economic and cultural context and the idea of contemporaneity. She observed that the paradoxical nature of the notion of contemporaneity within these white-background series depends upon the feeling of violence they produce, which overlaps the past with the present. Her comment continues pointing out how the first time she saw the portrait she immediately thought: “this is a guerrilla fighter from the 1980s”. It was only some time later, when she knew more of Guatemala’s history, that she understood that this person belonged to the patrullas de auto defensas civil(PAC), that were created by the national army in early 80s as a central part of the counterinsurgency strategy. She also told me that this phenomenon of linking the Autodefensor’sportrait with the guerrilla happened very frequently to other expats that, like her, come to Guatemala to work in international organizations and NGOs. It was also very recurrent that when expats visited them almost immediately linked the Autodefensorportrait to indigenous peoples’ struggles or human rights causes or both.

On the contrary, “most urban Guatemalans that visited us barely noticed the portrait”, she said. After the interview I asked what could be the cause of this difference in the appreciation and the level of identification with the Autodefensor, and she responded something like:

They [urban ladino Guatemalans] see this scene every day, all around: An indigenous young man holding a gun is not something alien to them; it is something that belongs to their quotidian life; they are surrounded by them. Wherever they go in the city they see this same image. In their condos, their gated communities, the supermarkets, the shopping malls, their offices; all around they see this image of a young man holding a rifle or a shotgun.

I think that the kind of interpellation she felt in the presence of the Autodefensor’sportrait came from that moment of destabilization of representation itself. In the beginning she could not correlate this portrait with the face of Guatemala’s genocidal State. The first time she saw it, she projected a guerrilla fighter on to it. In addition, a celebrated American photographer made this portrait in the 1980s; this was a photographer who, in theory, was supposed to have witnessed the horrors of war and the consequences of the scorched earth strategy that lead to both genocide and the implementation of the humanitarian warstrategy. This was also a portrait that appears in Victor Perera’s book Unfinished Conquest, which, to some extent, is the first book that educatedexpatssee and read before they come to Guatemala. In other words, this portrait is already contingent to the possibility of some sort multinational circulation of Guatemala’s visual post-counterinsurgency culture. As Chauche told me onetime:

Everybody will fill up the white background with whatever they want to see. People tend to project themselves in photography. And they do this not only in my photography, but also in all kinds of photography. The only difference is that I provide the possibility to the public to make their projection in an explicit fashion, whereas other photographers exploit this condition without even knowing they are also projecting themselves. And this is something especially accentuated in war photography.

And this commentary and the recent experience produced such a crisis that it even endangered the completion of the documentary. This crisis was based in three different events at least. First, there was Don Manuel, who kind of liked us, but did not trust us very much, and saw in us the opportunity to get some extra cash. Second, the aspects related to our social positionality in relation to don Manuel (I believe every one of us was aware of our positionality in Guatemala’s structure of power.) This is basically what Andres remarked during the interview. And this is a very important sociological approach to the debate on social positions and dispositions and the production and reproduction of hierarchies and inequalities of power during these kinds of undertakings. This even included the presence of forms of utilitarian exchanges.

This was also something we discussed with Chauche and Maria Elena, when they explained to me the complexities inherent to this photographic project that has been going on for more than 30 years. During the time he instructed me in photography Chauche insisted on the importance of establishing forms of reciprocity with the photographed subjects, not only to reduce the asymmetries that exist between the photographer and the photographed, but also to increase the engagement of the subjects in the production of the photograph.

This translates in a photographic praxis in places like San Juan Atitan, where the first thing they do is to talk with the local authorities, to request their authorization to take the photographs and to always give them copies of the images (original b/w half format if possible, or digital copies when printed in situ). I had these appealing thoughts about the paradoxes of the concept of contemporaneity that emerged from this specific portrait (and the rest of the white background portraits) and how this opened a space of interpellation that fissured the possibility of representation among the people that eventually had the chance to appreciate it.

Like a kid in a candy store I wanted to cover all these aspects in the documentary and also in my dissertation. This, however, would have implied stoping the other projects I was working to finish my research goals in order to work exclusively in this specific project. And this would also have meant to radically change my research process. This process began as a research of Daniel and his notion of war photography. And I should not change that, even if the problematization of the reproduction of forms of utilitarianism was present in the trip. I was doing an ethnography of how Daniel creates a space of visibility with the white background that destabilizes the position of the observer. I could not afford to lose my way, I had started already collaborative ethnographic relationships with other projects and it would be completely irresponsible from me to abandon them. There was also the complexity that Chauche wanted a film that could help him to present his work in relation to the specific trips we made to find the Autodefensor.[1]

The gaze of desire: War photography and Interpellation

During this chapter I have shared my ethnographic experience in order to give elements to support the hypothesis that Chauche’s white backgroundphotography entails a form of non-representative aesthetics that destabilizes the unawareness that the subject occupies at the moment of contemplation of his white background portraits. My hypothesis, then, is that when Chauche eliminates the contextual background the subject has the chance to fill it with whatever he or she wants. This is what Chauche highlights when pointing out that people permanently project themselves in the photograph. The lack of a specific geographic or sociological context not only opens the portrait to any ideological production of meaning, but also opens the desired epistemological context.

Andrés was still in Guatemala. During those days we were having a discussion regarding the elements that should be included in the collaboration. As stated before, the basic components were supposed to be the old and the new photograph, a chronicle relating the process and the documentary film. One morning I was checking on my Facebook and a new event regarding the photograph happened. It was too good to be truth.

I do try to follow systematically the Facebook pages of post-counterinsurgency relevant personalities. One of them is Ricardo Méndez Ruiz, who directs the Fundación Contra el Terrorismo. This is the more active and virulent organization that today works actively to create public opinion in favor of former counterinsurgent military war criminals. This organization also works to produce public opinion against human rights and social activists. Part of their tactics is to play the Justice System to criminalize activists that struggle for social justice in Guatemala. That morning I was on my routine monitoring when I saw this in the Fundación contra el Terrorismo page:

In that moment I made the screenshot and sent an email with it to Andres and Chauche. Chauche wrote a message to Ricardo Mendez Ruiz asking him to remove the photograph from his Facebook page because it was not meant to be used in the way they were doing it. Some minutes later, Mendez Ruiz removed the photograph, but instead linked it from Chauche’s website and wrote a larger text glorifying the role of the patruyerosin Guatemala’s Civil War. It was intriguing that the iteration of the Autodefensorwas made by Ricardo Mendez Ruiz, and his Fundación contra el Terrorismo

It is fascinating to follow the trajectory of this portrait, from its origins in the 1980s until now, when the Fundación Contra el Terrorismo used it to promote its cause. Building upon the history of the Autodefensor’s portrait it is possible to appreciate how the lack of background and the intensification of the face in Chauche’s portraiture produces an effect in which people try to project themselves into the void that the background opens. When I propose that Chauche’s portraiture engages in a non-representational aesthetics I do not intend to argue that representation disappears completely from the photograph. Instead, I propose that several of the moments of representation are also accompanied by other elements constitutive to the relation of desire to aesthetics. And this is the aspect that invites us to transcend the mere phenomenological analysis and dig into some psychoanalytical ideas.

As Birgit said during her interview, the gaze of the subject interpellated her. This interpellation is something that allows linking Althusser’s (2014) notion of subject and Lacan’s (1978) conceptualization of the gaze. Instead of producing an interpellation by the authority who tells the subject “hey, you there!” the intersection of gazes between the public and the portrait brings to the foreground the reflection that every possible interpretation is proceeded by the subject’s desire.

And this is how I try to frame the notion of non-representational aesthetics, which transforms both the poietic and the cathartic element of the piece into a performative act, in which the subject is able to realize his or her belonging to a specific moment in time and space, by realizing that the image makes him or her see something beyond, which is based on the impossibility of knowing who the photographed subject is. Chauche’s portraits are not pointing in the direction of mimicking the life conditions of the photographed subjects, instead they produce a bare gaze in which the spectator realizes that what he sees in the portrait is nothing more than a virtual space, a mirror that reflects in front of another mirror and that whoever is that person on the photograph belongs to the realm of metaphysics. Isn’t this, in political terms, more radical than any possible representation?

Two gazes are crossed, but only one has the privilege to see, and what it sees is the reflection of its own desires, anxieties, fears, expectations. The gaze of privilege, when realizing this, it does not know what to do with the other gaze, the inaccessible one. That is the moment when representation crumbles and vanishes in the impossibility of accessing the real.

Conclusion

This chapter has contributed in understanding the impossibility of foreclosing the aesthetic regime. The research experience with Daniel Chauche yielded the possibility to problematize the idea of war photography as an exclusive documentary/observational process that reflects the real. This impossibility of representing the realproduced a kind of non-representational aesthetics that can be taken as point of departure in exploring the emergence of forms of dissent that destabilize the processes of depoliticization that counterinsurgency intended to generalize in the cultural field. By making transparent that desire is in the middle of representation Chauche’s white background photography re-opens the possibility of engaging in processes of radicalization of the political beyond the limits of the aesthetic regime. This is the emergence of the supplement that Ranciere considers to be in the center of the politicization, and can be understood as the need of problematizing the political positionality when producing politicized arts.